Over the last few years, I keep thinking that the penny has finally dropped – it’s the stakeholders that count! People in projects talk about stakeholders, even the project management associations talk about stakeholders, yet when you listen carefully, you start to wonder. Are the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of stakeholder engagement really understood?

One area you’d think was undeniably a stakeholder intensive process is the development of the business case. Surely this is critical to the stakeholders and the investors in the project? But no! Today, business cases are often written by specialists in writing business cases, or worse, the project manager, and often in parallel or even after the project has started.

One relatively recent improvement is that you find a whole section entitled ‘Stakeholders’ in a good business case. Yes, it has an entire section! But often, the content and purpose are problematic. It should neither be a list nor where stakeholder analysis is written up. What it should do is provide evidence in support of the three functions of any business case.

What are these three?

The first is to demonstrate that the project is worth doing.

The second is to prove that it is more worth doing than some of the competing projects. And the third is to provide the framework for all future business decision-making about the project.

To achieve these, the business leaders and investors in the project need to be convinced about:

- Desirability – is there evidence that the project is worth doing, and just as importantly, who thinks so? Are there legitimate stakeholders backing the project?

- Do-ability – is there a feasible case for delivering the outputs and outcomes? Planning is necessary before do-ability can be proven. Still, even at this stage, options analysis, level I costings, and the management case guide as to how likely it is.

- Viability – combining desirability and do-ability leads to an assessment of how viable the project is. Are the benefits risks and cost risks commensurate with the risk appetite of the critical stakeholders and the organisation?

So how does the stakeholder section contribute? What should its purpose be? If the business case is to deliver on its promises, you need to know, “Who wants what?” “How badly do they want it?” And “How committed are they?” Oh, and it’s helpful to know how universal the view is that this is an important and necessary expenditure even at this stage.

With that in mind, it becomes clear that there are four groups of stakeholders to be considered for inclusion in the Stakeholder section.

Stakeholders and the business case

Group 1: The accountable stakeholders

All projects need “somebody who cares”. An accountable stakeholder is a leader who cares enough that they are prepared to be held accountable for delivering the benefits and the return on investment for this project.

The one group of stakeholders that really matter are those leaders who are prepared to put their names against the case for action.

They are signing off on the desirability of the business case and their understanding of the risks associated with value achievement – they are underwriting the viability of the project. They have established to their satisfaction that the likelihood of the benefits being achieved is within the appetite for risk and believe that the return on the investment is acceptable or better.

So, the Stakeholder section must convince us that these stakeholders exist for this project and have the necessary commitment. Is a signature enough? Perhaps! But it’s more compelling when the project sponsor is required to write and then present the motivation for the business case to their peers – something I’ve seen in a few organisations. Though the company that placed a poster over the sponsor’s desk displaying his signed agreement to the project business case, I felt was being unnecessarily aggressive!

Bent Flyvbjerg, in his recent presentation and paper on the fallacy of the cost-benefit analysis (Flyvbjerg & Bester, 2021), emphasises how important it is that these stakeholders have some ‘skin in the game’. It certainly underpins genuine accountability. In discussing the endemic problem of under-estimated costs and over-estimated benefits in public-spend projects, he recounts an example of criminal charges being brought against a sponsor who signed off an obviously non-viable business case and urges other governments to follow suit.

Group 2: Consulted stakeholders

The second group to be included should be the individuals consulted before the development of the business case. Why? Because they form part of the evidence of why the business case is framed the way it is. I recently reviewed a newly implemented governance system for a large pharma company. Like all pharma, it had a complex authorisation structure in line with the high investments associated with their projects. What I found fascinating was the system’s focus on accountability – who signed off, who had been involved in the approvals and when. The whole process was entirely transparent and

traceable. It undoubtedly affected and underpinned the organisation’s culture. It certainly had engendered a less carefree, cavalier approach, though being risk-averse is not necessarily a good thing in a research-based company.

Knowing the sources are crucial to all three functions of the business cases. Has appropriate expertise been considered? Can biases be detected that reflect stakeholder agendas? Put simply – has the business case consultation been robust enough – have the risks to achieving the benefits as opposed to the gains been properly aired?

Group 3: The role-based stakeholders

The third group of stakeholders that should be present in the Stakeholder section are those individuals who will be involved in the governance of the project.

At this time, we won’t know them all. Some people are still to be appointed; the solution may not be agreed upon yet. But there will be some ideas about the resource areas (specific resources and types of resources) and what technologies are likely to be involved.

Why does that matter in the business case? Well, even at the business case stage, bottlenecks and constraints on resources can be identified. Try running a construction project which required large amounts of bitumen in South Africa during 2010-2012; try running a business project which demands input from change weary users; try running a project with a sponsor who is already committed to four other projects.

These are all non-starters – and you can know it right from the start. When fulfilling the functions of the business case, you must eliminate non-feasible solutions without limiting the viable options. In this way, the risk profile of the project simplifies.

I don’t know if you noticed, by the way, the unwritten assumption I made here in the second paragraph above. The business case is not a vehicle for documenting the solution. It is where options are laid out and recommendations made. Too often, a commitment is made to a solution. In that case, it’s not a business case you are writing or reading – it’s a force majeure!

Group 4: The agenda-based stakeholders

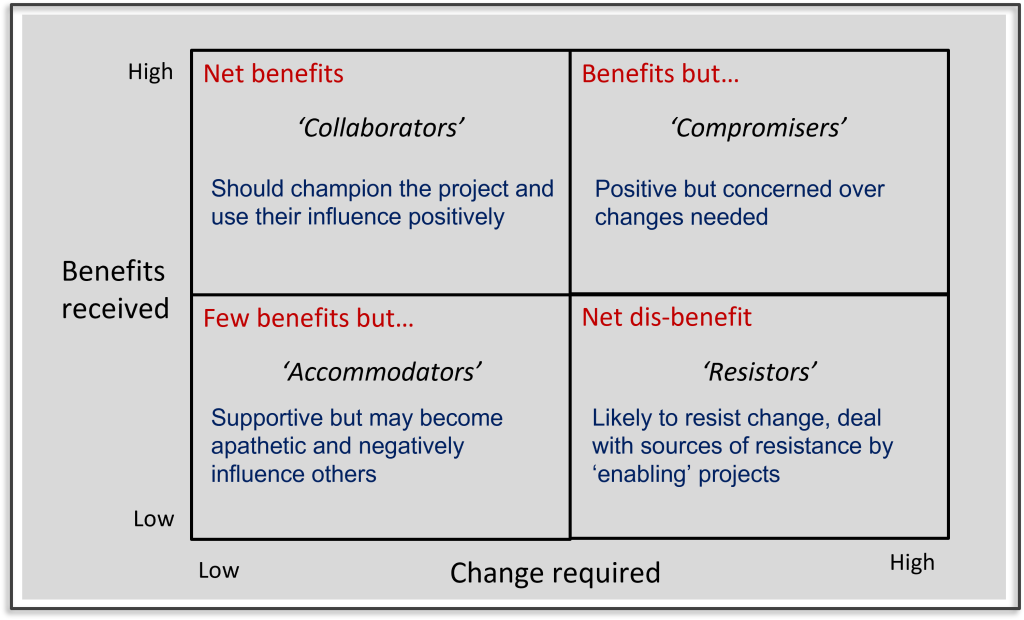

Finally, we have the fourth group – the agenda-based stakeholders. These people may not have a role in the project’s governance, but they have strong feelings about the project and can significantly impact its success.

Agenda-based stakeholders are difficult to find sometimes, not least because they tend to hide until the most inconvenient moment! But it’s worth the effort. One place to start is to look at net winners and losers from the project’s outcomes – not just the benefits.

You need to include this group, not with a detailed stakeholder analysis, because that is a planning process, but as an aid to understanding exactly how viable the project is likely to be. The business case, to fulfil its purpose, should capture the potential levels of antagonism and support towards the project. Too many stakeholders with opposing views can quickly push the project into the non-viable category.

Never mind the numbers – it’s the stakeholder commitment that counts!

Some of you are probably thinking right now that you don’t do anything like this, and it doesn’t really matter because, after all, a business case can be boiled down to a spreadsheet of numbers. Costs on one side, benefits, particularly financial benefits on the other – and once you juggled with them enough, the answer lies in plain sight.

If only that were so!

In a series of studies going back to 2003 and as recently as 2021, Flyvbjerg et al. have shown that in publicly funded projects:

…the traffic estimates used in rail infrastructure development decision-making are highly, systematically, and significantly misleading. Rail passenger traffic forecasts are consistently and significantly inflated…

…decision-makers are well advised to take any traffic forecasts that do not explicitly consider the risk of being very wrong with a grain of salt. For rail passengers, and especially for urban rail, a grain of salt may not be enough.

It’s not because publicly funded projects are poor or worse than commercial and industrial projects; it’s because the numbers are available for analysis.

In 2021, Flyvbjerg & Bester published their research into 2,062 public investment projects and reported that:

We found a fallacy at the heart of conventional cost-benefit analysis: forecasters, policymakers, and scholars tend to assume that cost-benefit forecasts are more or less accurate, when in fact, they are highly inaccurate and biased, at an overwhelmingly high level of statistical significance. In public capital investing, the fallacy results in average overestimates in ex-ante benefit-cost ratios of 50 to 200 per cent, depending on investment type. Individual estimates of benefit-cost ratios are routinely off by much more than these averages.

So, if you can’t trust the numbers, what can you do? Is this a counsel of despair? Not at all! You do what every business has always done, trust in the rational judgement of its leaders, experts, and advisors. And how do you ensure it is a rational judgement?

Well, Flyvbjerg & Bester suggest four pieces of advice. Two are of interest to me as they focus on the importance of stakeholders. These two are:

- Introduction of skin-in-the-game for cost-benefit forecasters – my stakeholder group 1

- Adaption of cost-benefit forecasting to the messy, non-expert character of democratic decision making – my stakeholder groups 2 and 4

The second one means that you must first establish what is valued and how valuable it is to the business and its customers (government and the public). You then determine how possible it is to achieve that value using an agreed-upon approach by informed and interested parties you trust. You make pretty sure you’ve considered the potential downsides, and then you gain commitment from the individuals charged with delivery.

Oh wait! I’ve just described a business case, but one that puts stakeholders in pride of place. Not a business case that uses numbers to fallaciously describe the future, but one that makes the stakeholders the focal point of the document. A business case that makes it clear that their contributions form the basis upon which the decision to go or not is made.

Sources

Flyvbjerg, B., Bruzelius, N., & Rothengatter, W. (2003). Megaprojects and risk: An anatomy of ambition. Cambridge university press.

Flyvbjerg, B., & Bester, D. (2021). The Cost-Benefit Fallacy: Why Cost-Benefit Analysis Is Broken and How to Fix It. Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, 1-25. doi:10.1017/bca.2021.9